WWI Commemorative Service

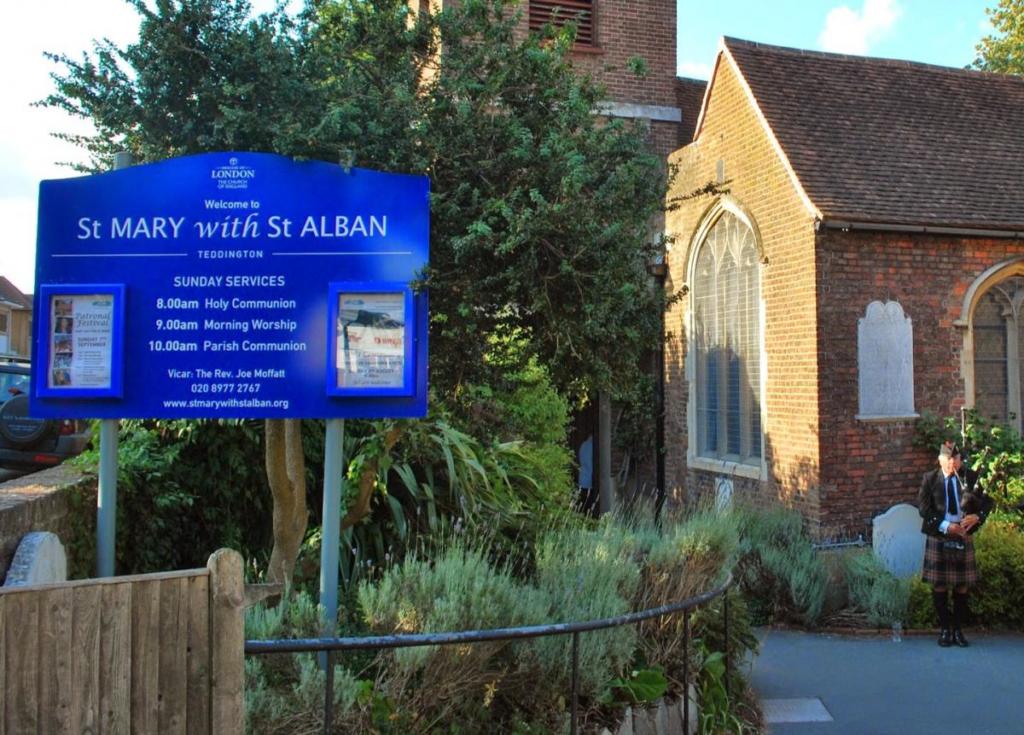

On the evening of Sunday 3rd August, instead of the church bell being rung, the congregation were called to worship by the sound of a lone piper playing a series of laments. The occasion was the Service of Commemoration for the Centenary of the outbreak of World War 1. The plaintive pipe-music set the tone for what was to be a reflective and very moving service. Our Vicar, Joe started by welcoming everyone, including the Lady Mayor, Jane Bolton, and her entourage and representatives from the RNLI, the Sea Cadets and the Royal British Legion. The uniformed representatives carried their Standards to the High Altar during the Processional hymn. Joe said prayers for all those who died and suffered in the war and asked for God’s peace and healing on us all.

Philip Skerrett read a short piece that he had written about the pipers of the Scottish regiments (many as young as sixteen) who, unarmed, had led their comrades ‘over-the-top’ across no-man’s land playing rousing music. Their moral-boosting role soon made them obvious targets for the German machine-gunners. Organist Peter Mence played Vaughan Williams’ ‘A New Commonwealth’, during which four candles, representing the four corners of the world, were lit and placed on the altar. Then four poems concerning the war were read by members of the congregation. At the end of each poem one candle was extinguished, symbolising Sir Edward Grey’s statement that ‘the lamps are going out all over Europe’. Between the reading of the poems we sang the hymn ‘It came upon the midnight clear’ usually associated with Christmas but appropriate in this context because it calls upon mankind to ‘hush the noise, ye men of strife / and hear the angels sing’.

Our own Mary Hawes and The Rev Jack Knill-Jones, Vicar of St Peter & St Paul then read out the Roll of Honour, the names of the fallen from World War 1 which are inscribed on memorials in Teddington. Between ‘The Last Post’ and ‘Reveille’, both played perfectly by trumpeter Jonathan Spencer, there was a two minute silence in which to remember not only the dead but also those left wounded and disabled and also to reflect on the consequences of that terrible war.

The Sermon was given by Rev Canon Dr Michael Brierley, Precentor of Worcester Cathedral. He took as his theme the parable of the ‘Lost Sheep’ from the Gospel reading and likened it to the story of Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy a British Army Chaplain in the First World War, who, with no concern for his own safety under heavy enemy fire, roamed no-man’s land searching for the wounded and helped them to the dressing-stations. His bravery earned him the Military Cross and his dispensing of Woodbine cigarettes and spiritual aid earned him the nick-name ‘Woodbine Willy’. The Service ended with a commitment to peace and to live as good neighbours.

The mechanised horrors and human tragedies of World War 1 were in complete contrast to this beautiful and contemplative service with which it was commemorated. The congregation had an opportunity to compare their reflections on the event over drinks served in the churchyard after the service on a lovely Summer’s evening.

Terry Brown

A sermon on Luke 15.4-5.

(St Mary with St Alban, Teddington,

6.30 pm, Sunday 3 August 2014 –

Commemoration of the Centenary of the First World War)

No one told the driver. Archduke Franz Ferdinand survived an assassination attempt in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. The bomb missed his car, he got to the town hall for his reception, he changed schedule by deciding to visit in hospital those whom the bomb had injured; but no one told the driver. The driver continued as planned. And when the shout came to him to stop and reverse, in order to go in the revised direction, that’s what gave Gavrilo Princip his chance, and set those fateful 37 days in motion. The first tragedy of 1914 was that no one told the driver.

Then there was the tragedy of those 37 days themselves. You may have seen the BBC documentary drama entitled ‘37 Days’ and broadcast in March – very little happened for three weeks after the assassination; diplomats had very little sense of the precipice of which they were on the edge, before being overtaken by events unfolding with terrifying speed and in unforeseen directions.

There was the tragedy that most people expected the war to be brief, for troops to be home by Christmas, rather than, after the war of movement had within forty days run its course, being locked into the bloody stalemate of the trenches. There was the absolute tragedy that so few had any idea of what industrialised warfare would be like – the utter absurdity of cavalry in a world of mortar shells – dug-outs, machine-guns and the Somme almost waiting to happen.

The First World War was perhaps one of the biggest tragedies in human history, if we define tragedy as ‘unwanted calamity’ – unanticipated, undesired and catastrophic. It’s a tragedy which affects so many of us, because our great uncles or grandfathers or grandmothers were caught up in it in their various ways. The dean of Worcester Cathedral was telling us that as a young clergyman he met an elderly parishioner who had never married: ‘all the men I danced with,’ she said, ‘got killed.’ All of our forebears lived through it; so many of us have some sort of story connected to it – that’s partly why this centenary seems to be resonating with people so deeply – and it’s a tragedy that has scarred not only our personal lives, but also our landscape, as well as of course the landscape of the continent, with a memorial if not a cemetery in every human settlement – beautiful scars in some places, but scars nonetheless.

It’s important for us, I believe, to think of that war in terms of tragedy, because there’s a religious dimension to tragedy which can help us enormously. The religious question, the theological question, the question of faith is to ask where God is, in all this senseless waste; and the type of answer that we give to that question affects what sort of human beings we are and what sort of human beings we become. My mother subscribes to what theologians would call a Calvinistic view of providence – the name doesn’t matter – it’s the idea that God is in complete charge, and that whatever happens in life is the divine will, even if we can’t understand it. The image is of God on a throne, supremely above and sublimely removed from conflict, while at the same time directing it.

The vicar of a parish in Worcester, who became the most famous British army chaplain of the First World War, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, had a different view – he wrote about the idea of God as supremely aloof in his book The Hardest Part, published in 1918. He wrote in striking words, ‘I want to kill the almighty God,’ he said, ‘and tear him from his throne.’ He knew deep within his soul that God was not aloof, unmoved, ordering things about from a comfy chair like a film director. The definition of tragedy as an unwanted calamity points us in the same direction, for it implies that there are things that happen in the world that may be unwanted even by God as well as unwanted by humanity. That very much changes the image of God for the person of faith, from the idea of a monarch or film director, reigning aloof, untouched and supreme, to something else.

That alternative way of imagining or conceiving or picturing God, an alternative way of locating or placing God in all this tragedy, a more helpful and fruitful way, is provided by something in which Studdert Kennedy was involved at the Front. On 15 June, 1917, he was in a collecting post for the wounded on the Ypres salient, not far from the front line – a little concrete shelter big enough for ten men and crammed with twenty. A boy in a corner with a badly shattered thigh was yelling and moaning by turns for something to stop the pain. This went on for over an hour while they were being shelled by guns. Someone had to go for some morphine, and Studdert Kennedy went, running from shell-hole to shell-hole and taking cover in between. He got the morphine, rescued a number of people from No Man’s Land, and for what he did on that occasion, was awarded the Military Cross – you can read the words of the official citation for that award in your orders of service.

That, it seems to me, is a key image, the image of this person who goes out into No Man’s Land, and does not stop or rest, until every wounded creature has been brought safely in. It’s exactly the same image, only in different clothing, as Jesus’s parable of the lost sheep, which we heard in our gospel reading: God is the good shepherd who goes out into the night, into the wild, into the danger zone, and does not cease or come back, until whatever lost sheep are out there, have been brought safely home.

Notice that the shepherd can’t stop the sheep from wandering; the power of the shepherd is limited; the shepherd is not in total control. So, that parable seems to be saying, God is not in total control of what happens in the world – final control, perhaps, but in the meantime, things may happen – tragedies – which are not even in the will of God. God’s power does not consist in doing whatsoever God likes from the seat of some high and mighty throne – that’s not real power at all. No, God’s power consists in something far more powerful – God’s ability not to stop, not to cease, not to rest – God’s infinite capacity, we might say – to redeem, bring in, carry home, whatever sorry state creatures have got themselves into, whatever sorry creatures are out there needing to be found. The world is, if you like, a great No Man’s Land, where all of us are wounded, there are any number of fractured and broken situations needing loving care and attention and repair. And what the parable of the lost sheep points to, what Studdert Kennedy’s action at Ypres points to, is a God whose power, whose love, consists in an infinite capacity to restore and redeem; a God who will neither cease nor rest until every last fragment of wounded creation has been brought safely in.

It’s desperately important, what sort of God we have in mind, this question of what sort of image or picture we have when we talk of God – because we tend, ourselves to become the image of God that we hold. If we think of God in one way, we tend to shape our own behaviour on that same model. People who hold a very monarchical picture of God, a very controlling God, either become very controlling themselves, or subservient to other people’s controlling natures. People, on the other hand, who hold to this God of infinite capacity to redeem tragedy, can be fellow-workers, co-labourers, with God in helping to repair and restore whatever tragic situations they come across in their daily lives. If we keep in mind the picture of God painted for us by Jesus in the parable of the lost sheep, the picture embodied by Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy in his action of 1917, the picture of God who is not aloof or apart from us, but with us, alongside us in all the tragedy of creation, working with us with infinite capacity to restore and to redeem, then there is, I believe, great hope for the world’s redemption.

If the First World War teaches us that much – the sort of God that God is – then out of that profound and terrible tragedy, some small grain of redemption will have been wrought from it in our own lives. God grant you and I to be people who work with God in searching for and bringing home every last lost and wounded creature, this First World War centenary and evermore. Amen.